Introduction

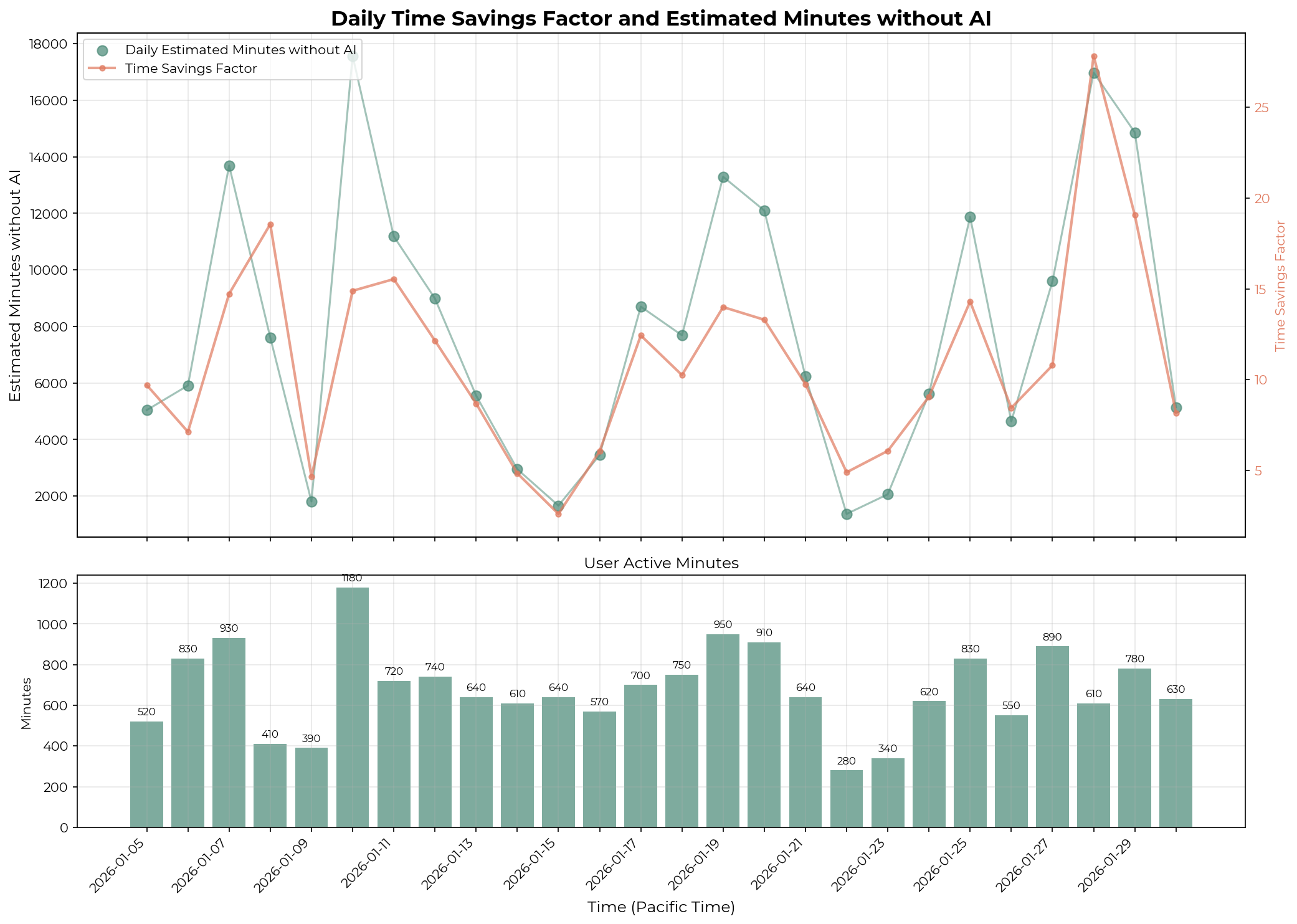

Human uplift studies like the one we did in 2025 are becoming more expensive as working without AI becomes increasingly costly. In this post, I investigate whether coding agent transcripts could serve as a cheaper alternative for estimating uplift. I prototyped this using 5305 Claude Code transcripts generated in January 2026 by 7 METR technical staff1. I used an LLM judge to estimate how long each task would have taken an experienced software engineer without AI tools, then compared that to the time people actually spent on these tasks to calculate a time savings factor.

Takeaways

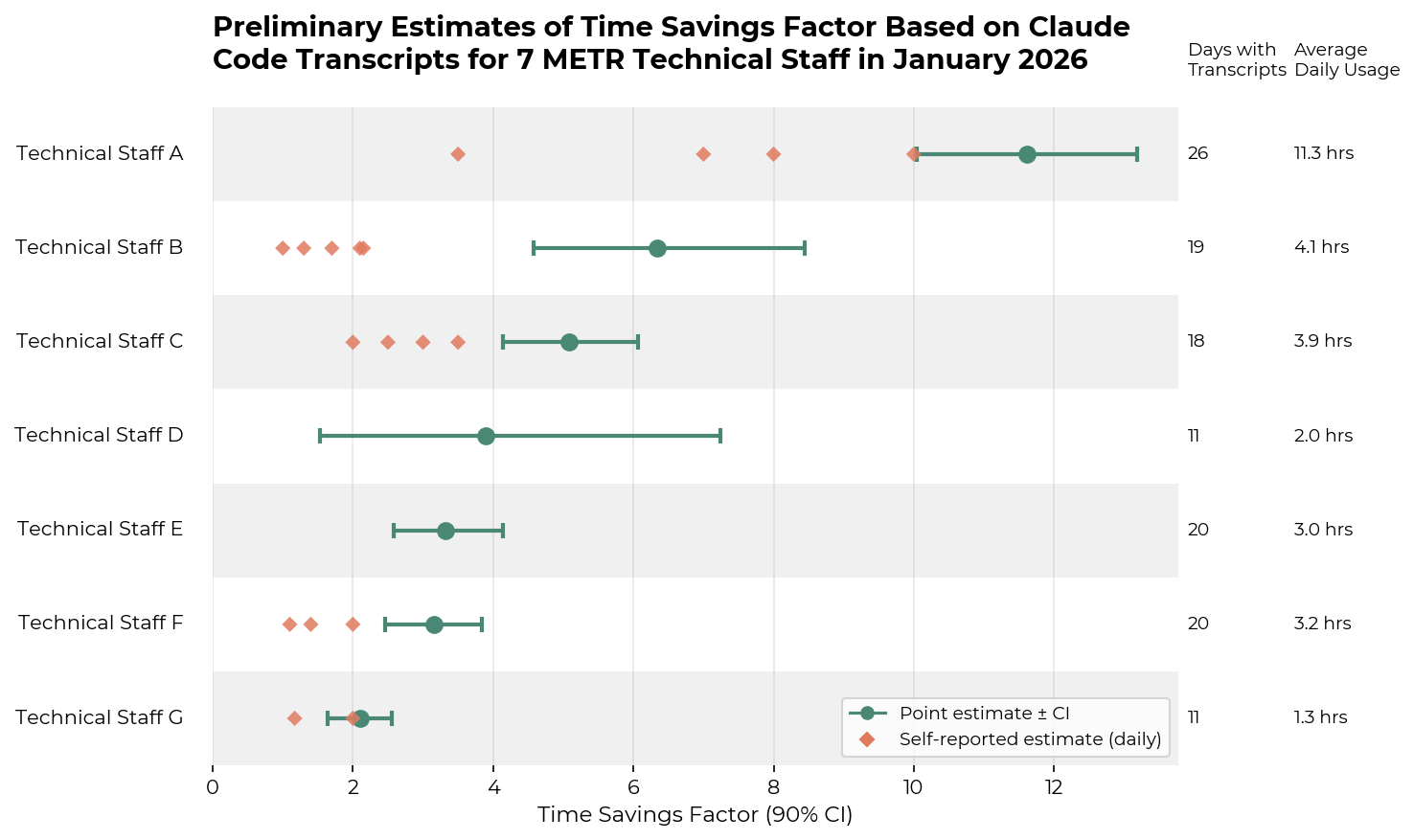

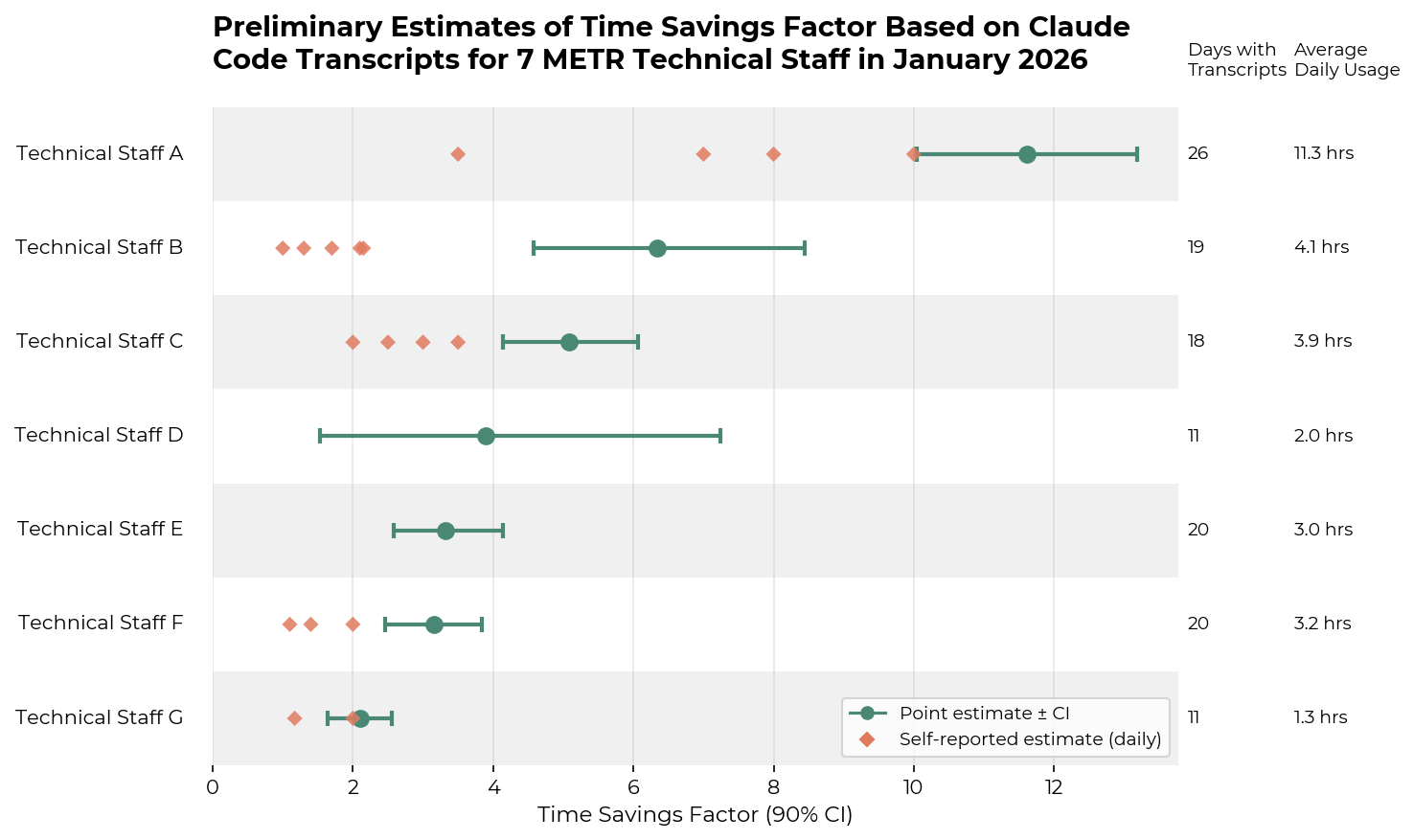

- This method estimates a time savings factor of ~1.5x to ~13x on Claude Code-assisted tasks for 7 METR technical staff in January 2026 – though this result comes with substantial caveats. I believe the true productivity multiplier is substantially lower, and the time savings factor is a soft upper bound for the true uplift that the individuals experienced.

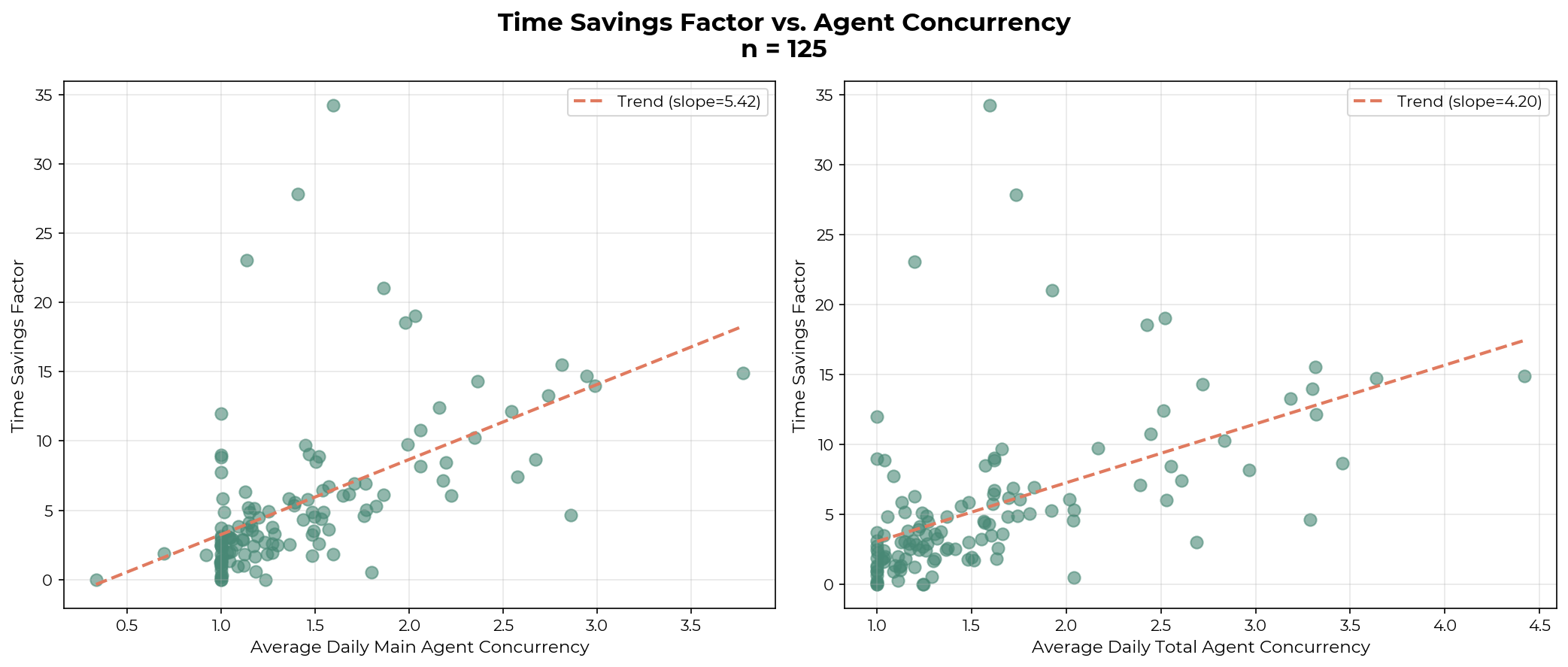

- Increased agent concurrency may contribute to a higher time savings factor on the Claude Code-assisted task distributions.

Limitations

- The time savings factor on the coding agent-assisted task distributions does not equal the productivity multiplier. People likely do not create 10x as much value with AI, even if we observe a 10x time savings factor on tasks that people do with AI. I believe the time savings factor overestimates AI-enabled productivity gains for reasons including:

- Task Substitution. With AI assistance, people sometimes complete tasks they wouldn’t do otherwise, such as making nice-to-have tools. These tasks tend to deliver lower counterfactual value, even if the observed time savings factor on these tasks might be high.

- Task Selection Effects. People don’t spend their entire workday using AI—they use it only on tasks where they expect it to be helpful. Since coding transcripts exclude tasks people do without AI, the time savings factor likely overestimates total AI-enabled uplift.

- Pre-existing Worker Specialization. While the LLM judge estimates are for “experienced software engineers”, individuals typically do tasks they specialize in, and thus take less time than an experienced SWE on average. Therefore, the measured time savings factor probably overstates their actual time savings.

- Limited LLM Judge validation. The LLM judge used to estimate human task completion time without AI is validated only on 34 ground truth labels, and may not generalize.

- Limited data sources. I only analyzed Claude Code transcripts from 7 METR technical staff within a single month. This excluded work done with other coding agents, chat interfaces, and non-coding AI assistance, capturing only a slice of AI-assisted work.

- Limited ability to identify human-typed messages. I estimate the time people actually spent working with Claude Code based on human-typed messages in transcripts. However, when users engage in advanced workflows, such as spinning up new agent sessions using Claude Code, the model-generated user messages may appear indistinguishable from actual human-typed messages. A spot check of 100 randomly sampled “human-typed” messages from our most advanced user found no obvious misclassifications, so this likely does not significantly affect the results in this post.

Methodology

The time savings factor is the ratio between the estimated task time without AI and the estimated task time with AI

My definition of the time savings factor follows Anthropic’s recent work on estimating AI productivity gains from Claude conversations.

time savings factor = time estimate without AI / time estimate with AI

I calculated the time savings factor daily for each individual, where:

- Time estimate with AI is the amount of time the staff member spent working on tasks with AI assistance that day. I estimate this by summing 10-minute windows that contain at least one user-typed message in the transcript. When a user is active in multiple concurrent sessions during the same window, the window is counted only once, rather than being overcounted across parallel sessions.

- Time estimate without AI is the hours an experienced software engineer would need to complete the same tasks without AI assistance, estimated by an LLM judge given a summarized transcript.

LLM Judge’s estimated time without AI via compressed transcripts

I compressed lengthy transcripts by summarizing assistant actions and outputs with GPT-4o while preserving code diffs. GPT-5 then analyzed the compressed transcript to identify successful and failed subtasks and estimated the time an experienced, high-context engineer would need to produce the net successful output.

To only include the time required to produce the successful outputs, I instructed the judge to exclude the following from time estimates2:

- Failed tasks: Work with explicit user disapproval.

- Agent overhead: Setup tasks like configuring subagents and skills, managing agent sessions, or building multi-agent infrastructure—work that wouldn’t exist without AI.

- Abandoned work: When the user requests A, then pivots to B, the time for A is excluded.

- Self-explanation: Summarizing or explaining code written in the same session, since this would not be required if engineers wrote the code themselves

- Spurious error correction: Fixing trivial bugs introduced by the agent that an experienced engineer wouldn’t make.

- Verbose planning: For extensive design documents, estimate the time to reach the design, not to write detailed documentation that the agent produces.

See Appendix A for the full prompt.

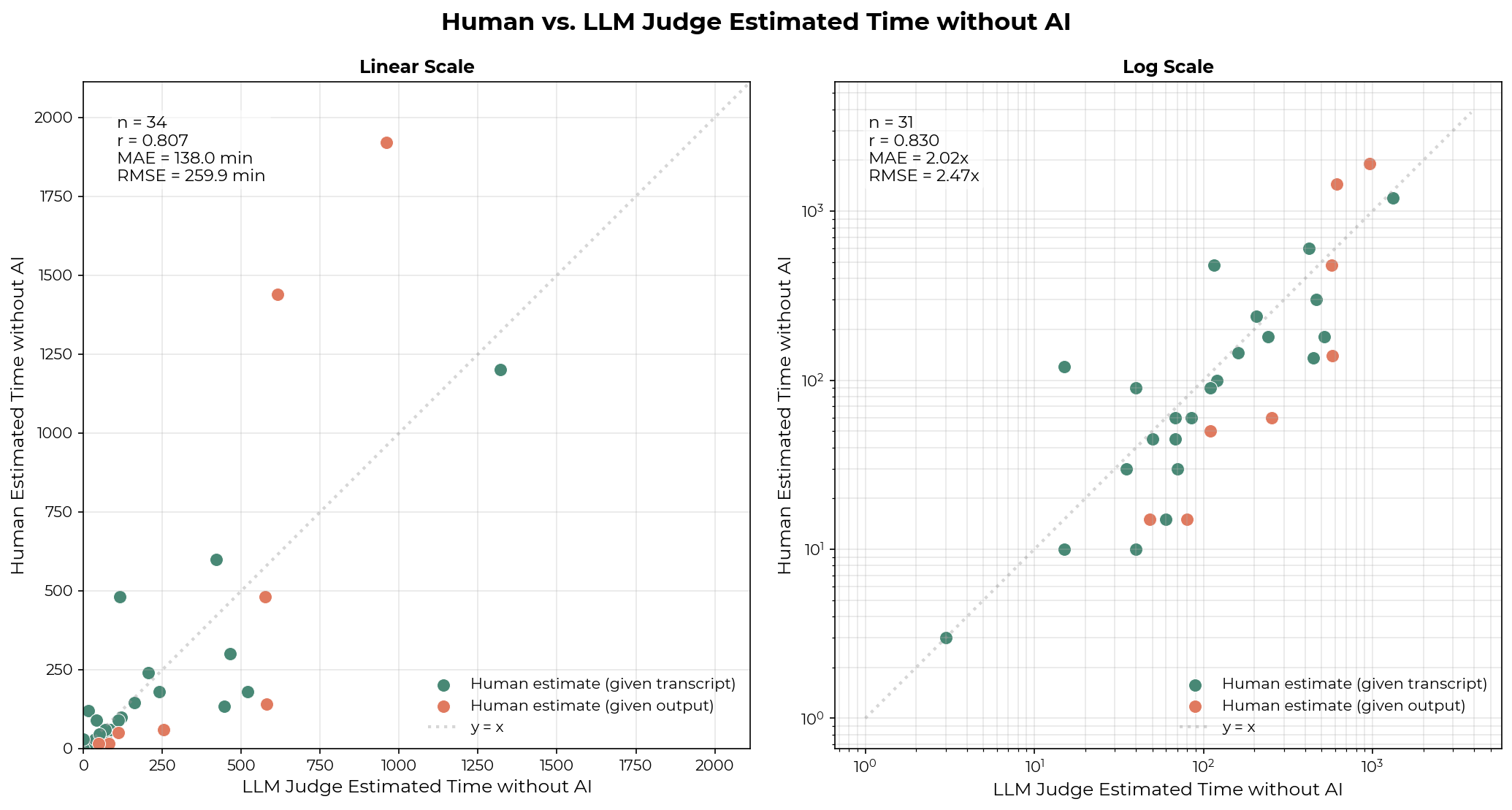

Validating LLM Judge’s time estimate without AI

Estimating task time is difficult even for humans with full context. I validated the judge against 34 human estimates: four staff members estimated time for 26 of their own transcripts, and one staff member estimated time for 8 transcripts based only on the resulting PRs and issues. These transcripts span feature additions, code exploration, greenfield projects, refactoring, and bug fixes, and some include failed subtasks.

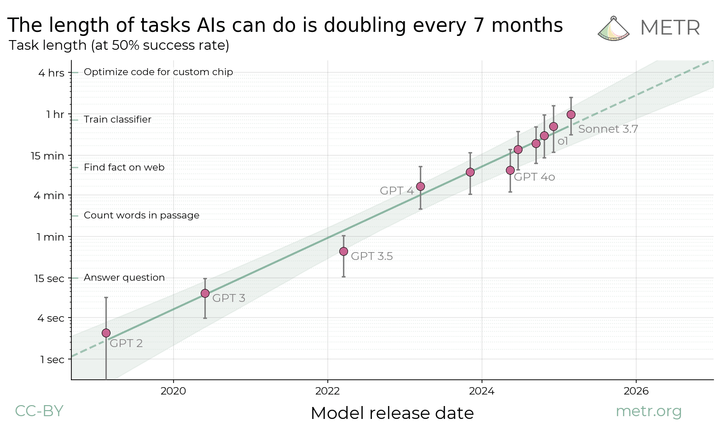

On average, the LLM judge’s predictions fall within 2-3x of human estimates, with occasional larger misses. The r_log is 0.83, higher than the human r_log of 0.67 and Claude 4.5 Sonnet’s r_log of 0.46–0.48 reported by Anthropic on time estimates for software development tasks from JIRA tickets.

However, this validation is limited – 34 samples are small. Additionally, while some human-labeled samples include failed tasks—providing partial signal on the judge’s ability to identify subtask success and failure—I did not explicitly validate this step, which introduces additional uncertainty. View example transcripts, human estimates, and LLM estimates here.

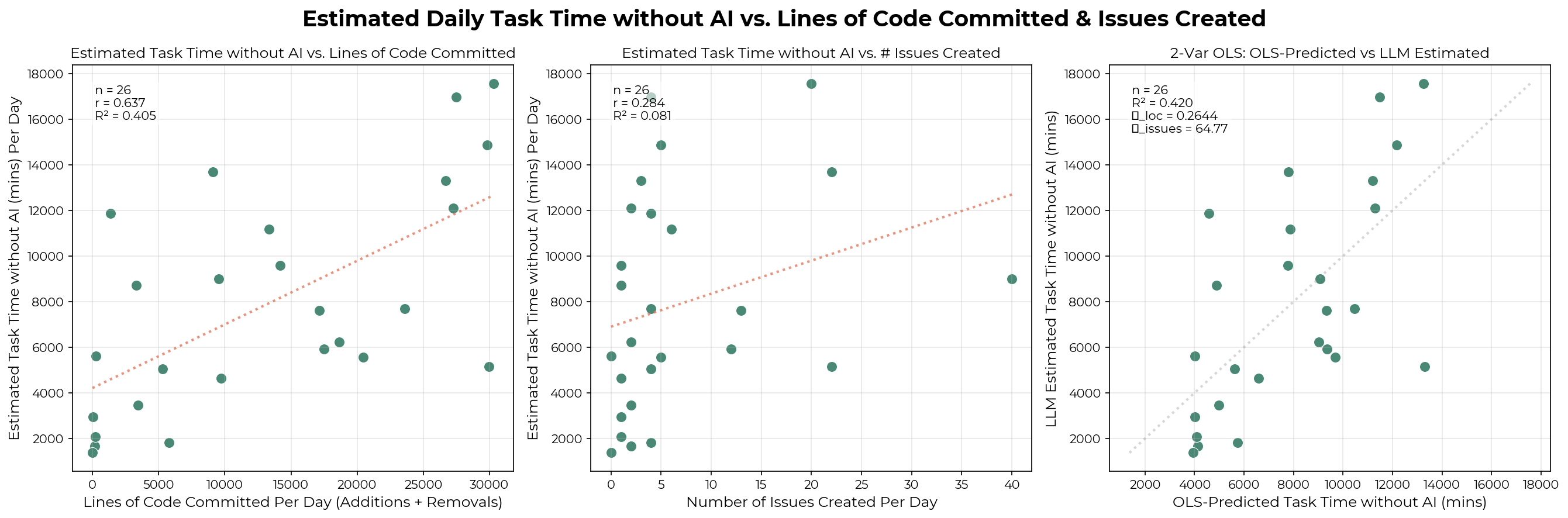

Estimated task minutes also moderately correlate with delivered outputs. I collected the lines of code committed (additions + deletions) per day for one technical staff member in January. The lines of committed code explain ~46% of the variation in estimated task minutes per day. Adding issue counts provides a negligible lift (~1.4%). It’s not surprising that there isn’t a stronger correlation: lines of code vary in difficulty, some code is never committed, and commits don’t always land on the same day the work was done.

Based on these results, I believe the judge produces reasonable estimates for our task distribution. Given the limited judge validation and 2-3x error range, the individual time savings factor should be interpreted as approximate rather than precise. However, they should help us distinguish worlds where individuals experience 1x, 10x, and 100x time savings.

Results

Empirically estimated time savings factor is between ~1.5x and ~13x on these transcripts. This serves as a soft upper bound for both (1) the productivity multiplier on Claude Code-assisted tasks and (2) the individual’s overall AI-enabled productivity uplift.

Bootstrapping over the daily time savings factor for each individual, we observe time savings factors between ~1.5x and ~13x on the tasks contained in the Claude Code transcripts.

For the following reasons, I believe the individual’s time savings factor is a soft upper bound on their productivity uplift for Claude Code-assisted tasks:

- People use AI on lower-value tasks. Anthropic’s internal survey reports that 27% of Claude-assisted work wouldn’t have been done otherwise. In our judge validation sample, 3.5 of 8 human-labeled PRs were work the staff member wouldn’t have done without AI, totaling ~47% of the estimated task time without AI for that individual. The methodology overestimates the productivity multiplier on Claude Code-assisted tasks when people use AI to complete low-value but time-consuming work (we call them “Cadillac tasks”).

- The LLM judge likely overestimates time without AI. In most of the 34 validation samples, the judge predicted longer times than humans estimated. There are several reasons why this might be the case:

- The LLM judge tends to assume a task is successful even if the user quits an agent session without explicit disproval.

- Staff tend to specialize in the tasks they do, completing them faster than a generic “experienced software engineer.”

- The judge evaluates individual transcripts in isolation, so it misses cases when progress is undone between sessions or when users start a new session as a retry of a previously failed session.

- Despite excluding explicit agent setup tasks, some agent-induced overhead is hard to separate—such as breaking work into granular steps a human would skip otherwise.

As further evidence, I asked several staff members to estimate how long it would have taken them to do the same tasks they did with Claude Code for a few days. See Appendix B for the exact survey question. All self-estimates fell below the bootstrapped point estimate, with most falling below the 90% confidence interval.

The additional reason below supports that an individual’s time savings factor is a soft upper bound on their productivity uplift across all work:

- Most staff don’t spend their entire day coding with Claude Code. For example, suppose a researcher spends 4 hours coding with Claude Code and 4 hours in meetings. Then, a 4x time savings factor on Claude Code tasks and 1x on everything else only yields 2.5x total uplift. However, this logic cuts both ways: if the same person also spends 2 hours on AI-assisted non-coding tasks (e.g., via chat interfaces) and experiences much higher uplift there, their total productivity gain could exceed the coding-only time savings factor. (Though based on anecdotal evidence, this is unlikely to be true for the staff participating in this study.)

Higher agent concurrency is associated with a higher time savings factor

Users can interact with Claude Code through one or more main agents, which can launch subagents in parallel to complete subtasks. I define concurrency as the number of active agents per person, reporting both the main agent concurrency and the total concurrency (main plus subagents). Daily average concurrency is computed as a time-weighted mean over periods when at least one session is active. Across the 7 staff members, a higher daily average concurrency (main and total) is associated with a higher time savings factor. Each point in the graph below represents one individual’s average concurrency on a given day.

Technical Staff A, who has the highest time savings factor, averages at least 2.32 main agents and 2.74 total agents on active days. The remaining staff average between 1.05 and 1.52 main agents and 1.07–1.57 total agents. See Appendix C for each individual’s average concurrency and Appendix D for qualitative descriptions of technical staff A’s workflow.

While causality can’t be established, I believe workflows optimized for agent concurrency may substantially increase the time savings factor for our technical staff. Though, as before, it is unclear whether this represents a genuine productivity improvement, because additional tasks completed via parallelism may be lower-value.

Discussion

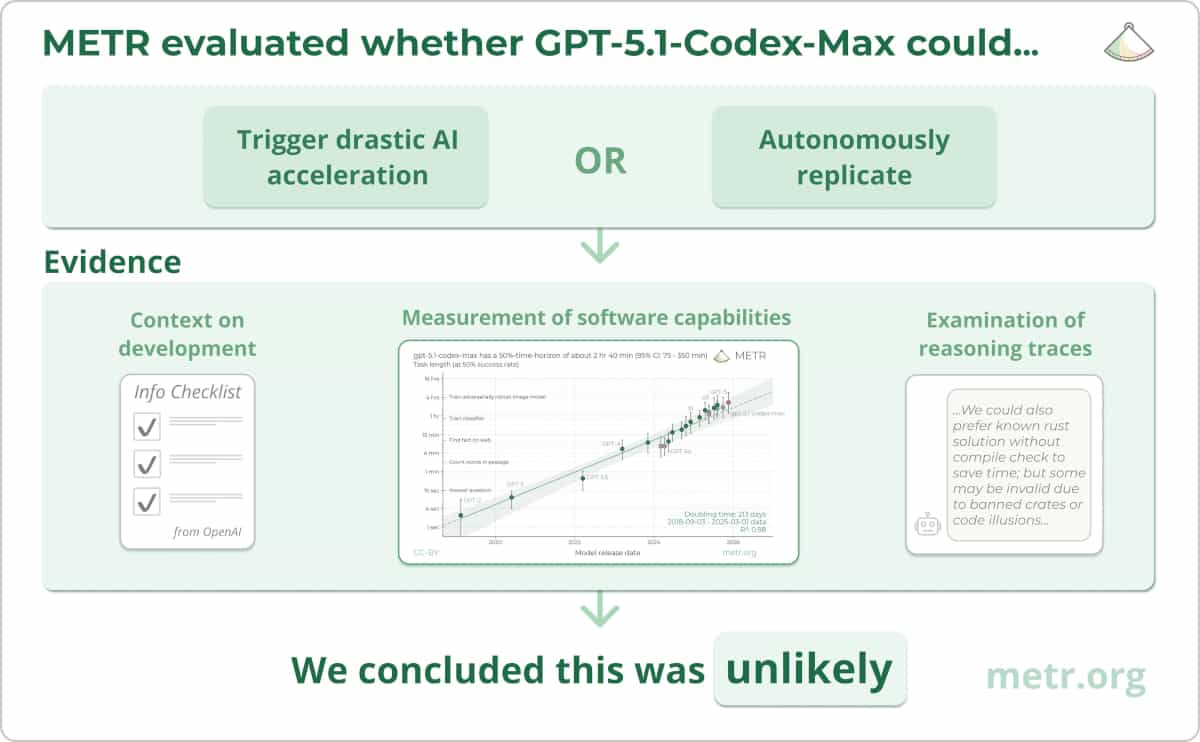

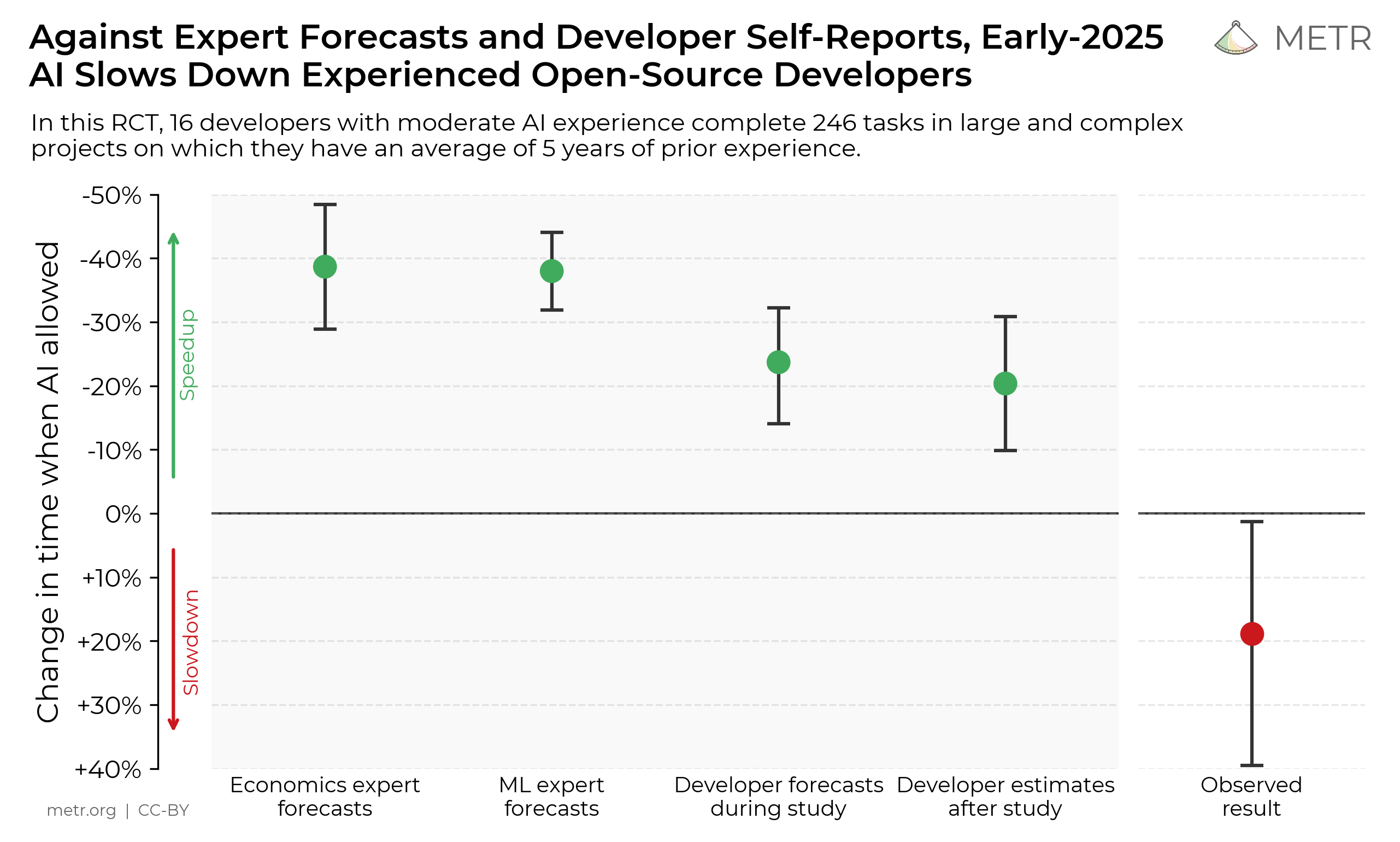

Uplift studies may underestimate uplift by not accounting for concurrency

METR’s human uplift RCT randomized developers to complete issues one at a time, with or without AI. The correlation between concurrency and the time savings factor suggests this design may understate AI’s potential impact. Future uplift studies we design should allow participants to work on multiple issues simultaneously, or assign larger issues amenable to concurrent agent use. Similarly, transcript-based analyses should account for parallelism rather than treating transcripts from the same individual as independent observations.

Measuring AI capabilities on real-world tasks via transcripts

Autonomous capabilities benchmarks have many limitations: they saturate quickly as models improve, they require significant upfront effort to create, and it’s hard to translate benchmark performance to real-world capabilities.

Real-world transcripts may be a complementary source of evidence in understanding autonomous capabilities. Relative to benchmarks, transcripts have several advantages:

- They’re generated naturally as a byproduct.

- They reflect the real-world, messy task distribution that we care about

- They can provide information on how people adopt AI in their workflows.

However, transcripts also have important limitations. Most significantly, people mostly use AI on tasks where they expect it to succeed. Observing high success rates on tasks in transcripts doesn’t tell us how well AI does on the tasks people don’t attempt with AI.

Despite the limitations, I believe transcripts can be useful for understanding autonomous capabilities. Impressive one-off demonstrations still provide genuine evidence of capability. Transcripts can also capture failure modes that curated benchmarks may miss.

Follow-up work

To build on top of this preliminary research, one could:

- Expand the analysis to serve not only Claude Code transcripts but also other command-line and IDE coding agent transcripts.

- Creating a better LLM judge and conducting further validation. The current judge has many known limitations, and should be validated on a larger number of human time estimates on a broader task distribution.

- Validate the methodology against an RCT uplift study. How well does the estimated time savings factor compare to the actual uplift ratio? Can we predict the uplift ratio based on the estimated time savings factor?

- Better understand the effect of task substitution. One might survey developers directly and ask how much more valuable output they deliver as a result of having access to AI tools.

- Analyze what kinds of tasks people use AI agents for, and how often agents succeed at different task types. This can help us better understand the trend of autonomous capabilities.

I would be excited for AI developers to conduct similar experiments on internal transcripts and inform the world about their speedup.

Conclusion

From this exploratory analysis on METR’s internal transcript data, we observe that people are substantially sped up on the tasks they use Claude Code for. The actual productivity uplift is likely much lower (but likely still positive) due to factors such as task substitution, task selection, and worker specialization. I believe that the empirically measured time savings factor for an individual serves as a soft upper bound for both their productivity multiplier on Claude Code-assisted tasks and across all work. Further research on coding transcripts would be valuable, and we would be excited to see AI developers publish empirical speedup measurements from their own transcripts.

Appendix A: LLM Judge prompts

This prompt is used to summarize assistant turns between human-typed user turns:

You are summarizing an AI coding assistant's turn in a conversation.

## Assistant Turn Content

{assistant_turn_content}

## Instructions

Provide a concise summary with exactly two parts:

1. ACTIONS: Describe what the agent did at a high level, NOT at the tool-call level.

Good examples:

- "Explored the codebase by reading configuration files and test files, then designed

a solution involving three new functions, and drafted a plan for user review"

- "Investigated the bug by running tests and examining stack traces, identified the

root cause as a race condition in the cache layer"

- "Implemented the requested feature by creating a new module with helper functions,

updating the main entry point, and adding comprehensive tests"

Bad examples (too granular):

- "Called Read tool on config.py, called Read tool on test_main.py, called Bash..."

- "Used Edit tool to modify line 42, then used Edit tool again to modify line 58..."

2. OUTCOME: What did the agent produce? Use one of these formats:

- "Drafted a plan to [brief description]"

- "Provided explanation that [brief description]"

- "Wrote code to [brief description]"

- "Asked clarifying question about [topic]"

- "Encountered error: [brief description]"

- "Completed research on [topic]"

Note: Code diffs are tracked separately. Focus on the narrative of what happened.

Use the summarize_turn tool to provide your summary.

This prompt is used for estimating time without AI:

You are estimating how long an experienced software engineer who has full context

would take to produce the NET SUCCESSFUL output of this coding session.

## Instructions

1. Read through the compressed transcript below and identify the overall task(s)

that the user is trying to complete. Each task might happen over multiple back

and forths between the user and the assistant.

2. Identify which user requests were successfully completed (user approved or

moved on). This might happen over multiple turns.

3. Identify which requests failed (user rejected, asked to redo, or explicitly

disapproved). Failed requests might also happen over multiple turns.

4. For SUCCESSFUL work only, estimate the human time to produce equivalent output

5. Failed/rejected work = 0 minutes (the output wasn't accepted)

6. All work that's related to coding agent setup should have 0 estimated minutes.

Such tasks include writing to CLAUDE.md files, finding a previous agent session,

setting up a subagent or skill, researching how to use coding agents, creating

infrastructure for using and tracking multi-agent orchestration systems, etc.

These tasks should all receive 0 estimated minutes, even if they succeeded. The

work is not part of the net output because if the human didn't use coding agents,

they would not need to spend time setting up the agents.

7. Sometimes the user would ask clarifying questions about the output, which is not

a failure, unless eventually the user provides failure signals.

8. Sometimes the user is not asking for code to be produced, but rather a plan or

an explanation. This is normal and should be considered as a valid task.

9. When code diffs are produced by the agent, use the code diffs in addition to the

task description to determine the complexity of the task. When looking at the code

diffs, don't just consider the diff quantity, since each line of code has different

complexity. Look at the code diffs and assess whether the changes that's made is

complex vs. simple for an experience software engineer to make, and make time

estimates based on your best judgment.

10. The compressed transcript would only show a summary of the agent's outputs unless

there's code written. Do not consider it a failure just because the summary was

shown for a task, and you cannot see the full output. Read the summary and use

your best judgment to decide whether the task was a success or failure.

## Success Signals

- User says "looks good", "great", "thanks", then moves to new topic → SUCCESS

- User says "now do X" building on previous work → previous work SUCCEEDED

- User moves to completely new topic without complaint → implicit SUCCESS

## Failure Signals

- User says "that's wrong", "try again", "fix this" → FAILURE

- User explicitly rejects or asks to revert → FAILURE

- User expresses confusion about incorrect output → FAILURE

## Example task 1

USER: [asks to build a feature]

ASSISTANT: [makes a plan to build a feature]

USER: [clarifies the plan and ask the assistant to edit the plan according to

additional requirements]

ASSISTANT: [modifies the plan]

USER: [approves the plan and asks the assistant to implement it]

ASSISTANT: [implements the feature, discovers a bug in its own implementation

and fixes it]

USER: [ask questions about the implementation]

ASSISTANT: [answers the questions]

USER: [moves on to a new task]

In this task, the feature was successfully built and the user moved on.

You should estimate the time it would take an experienced software engineer to

plan and implement the same feature. Even though the agent had a self-discovered

bug fix, this is agent overhead and should not be counted in the time estimate.

Only estimate the time to produce the final output: the plan AND the implementation.

## Example task 2

USER: [asks to build a feature]

ASSISTANT: [makes a plan to build a feature]

USER: [decides they no longer want to build this feature, asks for a new feature]

ASSISTANT: [makes a plan for the new feature]

USER: [approves the plan and asks the assistant to implement it]

In this task, you should estimate the total time it would take for an experienced

engineer to design the new feature, and ignore the time it would take to design

the original feature. Since we care about the NET work that got done; given the

original feature was abandoned, the engineer would not need to spend time on it.

## Example task 3

USER: [help me find the previous agent session that does X]

ASSISTANT: [finds the session]

USER: [summarize what that session implemented, then implement what it left out of

a particular issue description]

ASSISTANT: [summarizes, finds what the other session left out, and implements the

remaining issue]

If an experienced software engineer were to work on the task alone, they would not

need to spend time finding and summarizing previous agent sessions. You should only

consider the time it takes the engineer to implement the remaining issue, as that

is the NET work that got done in this session, ignoring the form factor of working

with coding agents.

## Example task 4

USER: [ask the agent to do something]

ASSISTANT: [tries to do the task, but fails]

USER: exits the session

We should assume that the request failed, and since the NET output was nothing,

the estimated time should be 0 minutes.

## Example task 5

USER: [random chats with the agent, not asking the agent to do anything]

ASSISTANT: [chats with the user]

USER: [asks about a new claude code feature]

ASSISTANT: [explains the feature]

USER: exits the session

Casual chats or agent setup related work produces no NET output, thus the estimated

time should be 0 minutes.

## Compressed Transcript

{compressed_transcript}

Use the tag_difficulty tool to provide your estimate.

Appendix B: Staff daily time savings factor self-estimates survey

This is the exact question I asked the technical staff at the end of their workday or the start of the following workday:

Consider all the work you did with Claude Code today, how many times faster did

you complete them with claude code than without? Answer with a number.

E.g. 2x means it would've taken you twice as long to do the same tasks that you

did with claude code today.

Appendix C: Individual agent concurrency statistics

Average agent concurrency numbers on a typical active day for each individual, alongside their time savings ratio, active days, and average number of active hours per day.

| Individual | Avg main agent concurrency | Avg total agent concurrency | Time savings factor point estimate | Avg hours using Claude Code per day | Num active days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Staff A | 2.32 | 2.74 | 11.62 | 11.32 | 26 |

| Technical Staff B | 1.52 | 1.57 | 6.34 | 4.05 | 19 |

| Technical Staff C | 1.4 | 1.48 | 5.08 | 3.87 | 18 |

| Technical Staff D | 1.17 | 1.25 | 3.9 | 1.98 | 11 |

| Technical Staff E | 1.19 | 1.29 | 3.33 | 2.99 | 20 |

| Technical Staff F | 1.26 | 1.38 | 3.15 | 3.19 | 20 |

| Technical Staff G | 1.05 | 1.07 | 2.11 | 1.26 | 11 |

Appendix D: Technical Staff A workflow descriptions

Qualitatively, Technical Staff A optimizes their workflow for concurrency in the following ways:

- He context-switches frequently between projects and uses git worktrees to work on multiple PRs in the same repo

- He front-loads effort on detailed plans and verification instructions, enabling agents to sometimes run autonomously for 1–3+ hours while he spins up additional sessions.

- He often has 10+ terminal sessions open at the same time to monitor multiple agents simultaneously.

- He employs techniques like “Ralph Wiggum,” which repeatedly feeds an agent a prompt file via a while true loop, allowing iterative improvement until completion. We note that this technique may artificially inflate total concurrency when the agent keeps running without doing real work.

See Appendix E for visualizations of Technical Staff A’s per-transcript uplift distribution and daily estimated minutes and time savings factor.

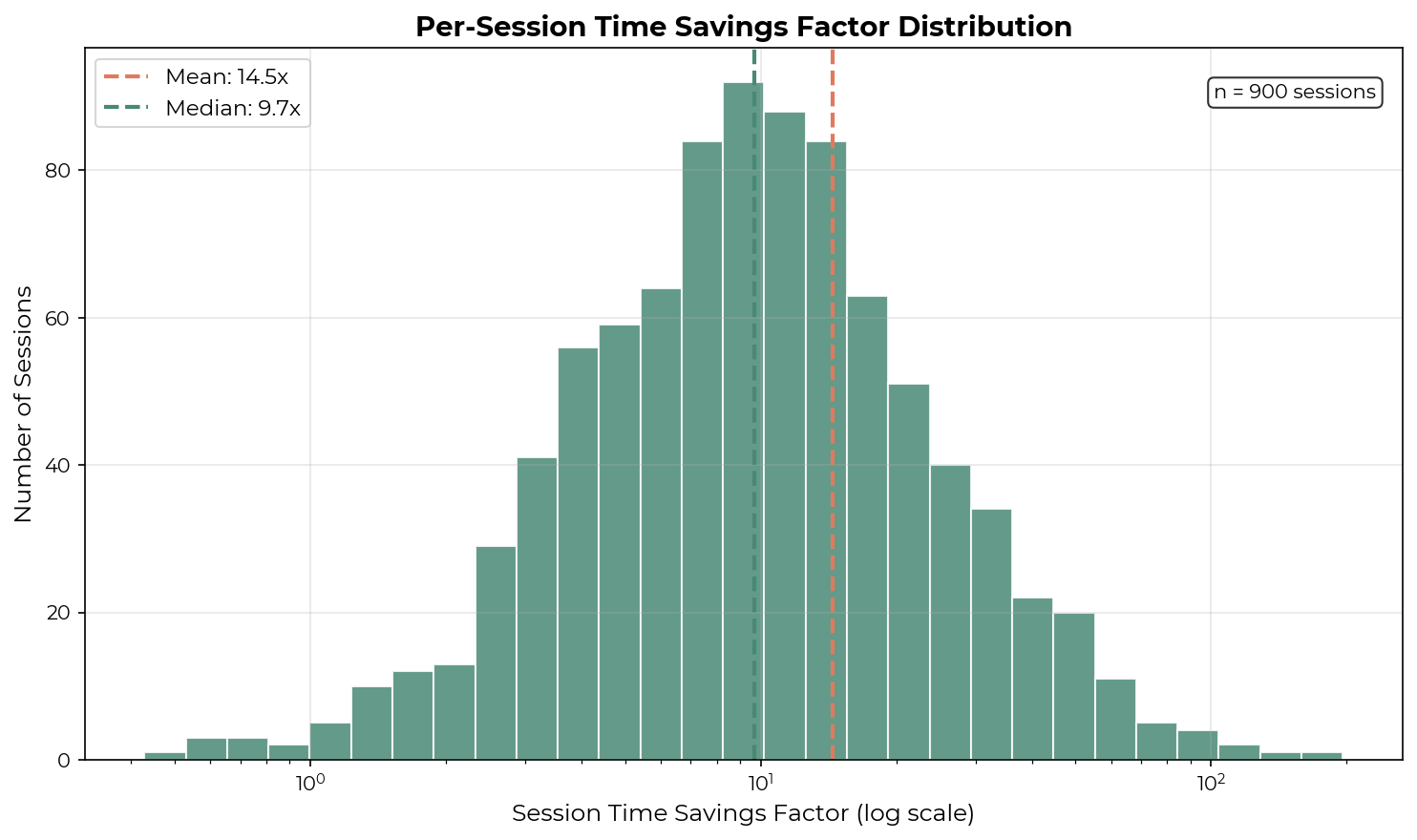

Appendix E: Detailed results for technical staff A

I briefly investigated whether Technical Staff A’s high time savings factor is driven by extreme outliers. To calculate per-transcript time savings, I computed concurrency-adjusted human-active minutes for each session. For each 10-minute window, I counted the number of transcripts the user actively interacted with (n), and attributed 10/n minutes to each transcript. This filtering excluded sessions with no active human participation, such as those running in Ralph Wiggum loops. I also excluded sessions where the LLM judge estimated <10 minutes without AI. The mean and median time savings factors are relatively close, suggesting that extreme values likely do not strongly influence the daily time savings factor.

I examined several transcripts with >100x time savings factors. The highest (196x) involved just 2 human messages and was estimated at 785 minutes without AI—the user asked the agent to evaluate 23 knowledge graph tools against an evaluation spec. Other high-uplift transcripts involved large implementations or refactorings based on pre-written plans.

The graph below shows the variations in the daily time savings ratio for the same technical staff.